Settler colonialism is not a story of friendly relations throughout. The confrontation with an unfamiliar other creates wariness and suspicion and often leads to violent outbursts in which noncombatants become innocent victims. Manhattan in the seventeenth century was no exception, as the events of 1643 show.

In the evening of February 25, 1643, soldiers and settlers of the colony of New Netherland massacred a large number of Native American men, women, and children belonging to Munsee nations on and around Manhattan. The victims were surprised in their sleep. They had assumed they were safe because they had recently sought shelter near New Amsterdam from Indigenous enemies. Dutch sources indicate that at least eighty and perhaps up to one hundred and twenty Munsees were murdered. The attacks took place on two locations. The first massacre, perpetrated by armed settlers, occurred at Corlears Hook in what is now Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The second massacre took place later in the night at Pavonia, a settlement located on the west bank of the Hudson River across from Manhattan. Soldiers of the Dutch West India Company, which governed New Netherland, committed the bloodbath at Pavonia. The two massacres ignited a Munsee-Dutch conflict known as Kieft’s War, which lasted until the summer of 1645. The war is named after Willem Kieft who was director of New Netherland during the war and whom historians hold responsible for the conflict.

Why?

Although American and Dutch historians have written extensively about Kieft’s War, one difficult question about the massacres at Pavonia and Corlaer’s Hook remains to be answered. Why did the soldiers and the settlers proceed with surprise attacks on the Munsee groups that consisted not only of warriors but also of women, children, and elders? In other words, why did the soldiers and settlers knowingly kill non-combatants? Racist attitudes, the destabilizing context of war, and peer pressure may have enabled the ordinary soldiers and settlers of New Netherland to kill defenseless Munsee men, women, and children in February 1643.

Views of Native Americans in New Netherland were complex but overall the Indigenous peoples were seen as culturally and morally inferior. Isaac de Rasière, secretary of the colony from 1626 to 1628, described the Indigenous people as “cruel by nature.” Calvinist ministers who worked in New Netherland considered Indigenous peoples to be heathens. As the colonial population grew in the late 1630s, incidents between colonizers and Munsees became more frequent. Cases of theft, brawls, and alcohol-related incidents involving settlers, soldiers, and Munsees were a matter of growing concern for the colonial government. Finally, the term “wilden” that the Dutch regularly used in correspondence and travel accounts when referring to the Indigenous peoples of New Netherland was another indication of the strong stereotypes held by the settlers and colonial officials. The term “wilden” referred to the widespread European belief in wild or savage humans who lived in the woods without any religion and civilization. Negative attitudes such as these made it easier for settlers and soldiers to dehumanize and kill Munsee people in 1643.

Fear

Another factor that enabled the slaughter of Munsee non-combatants was the growing fear among settlers, soldiers, and Kieft for a Munsee conspiracy against the colony in the early 1640s. This fear became a self-fulfilling prophecy because of the growing settler population as well as by the decision in 1639 to impose a yearly contribution on the Munsee communities living around New Amsterdam. This contribution was levied by Kieft in order to get the Munsees to help pay for the expenses of maintaining the fort and garrison at New Amsterdam. While Kieft claimed that the Munsees benefited from Dutch military protection, the Munsees strongly rejected the measure. They viewed themselves as sovereign nations who were perfectly capable of defending their own communities. Angry about Kieft’s contribution and the growing settler population, warriors of the Raritans, one of the Munsee nations, harassed several company employees in the spring of 1640.

Instead of pursuing accommodation and diplomacy, Kieft responded with a policy of intimidation and the threat of mass-violence. It is likely that he was familiar with the aggressive policies of the neighboring New England colonies who had waged a genocidal campaign against the Indigenous Pequot nation in 1637. Like the Puritan colonies in their war against the Pequot, Kieft believed that overwhelming force, including the targeting of Indigenous villages, was the best way to bring the “wilden” of the wider Manhattan region under control. Upon learning of the incident with the Raritans, Kieft dispatched a punitive expedition to their village. Several Raritans were killed and one was tortured. Raritan warriors retaliated by killing four settlers. Shortly after this attack, a man of the Wiechquaesgeck Munsee nation murdered a settler on Manhattan. Kieft now called for a special meeting with a new advisory board made up of prominent settlers in August 1641. In this meeting, Kieft asked the board whether they agreed that if the murderer was not extradited, “it is not just that the entire village from which he originates be laid to waste?” The advisory board agreed with Kieft that the murder had to be avenged. In the winter of 1642, a military expedition tried to attack the Wiechquaesgeck village at nighttime but failed to locate it. As the conflict continued to simmer, yet another settler was killed by a Munsee warrior from the Hackensack nation. By the spring of 1642, New Netherland was on the brink of war with no less than three Munsee nations.

Kieft and the settlers became firmly convinced that the Munsee nations were conspiring against them when hundreds of Hackensacks and Wiechquaesgecks suddenly appeared in the proximity of New Amsterdam in late February 1643. The exact circumstances remain unclear but Dutch sources indicate that the Mahicans, an Algonquian nation from the Upper Hudson Valley, had recently attacked the two Munsee nations. The Hackensacks and Wiechquaesgecks fled to Manhattan in the expectation that the Mahicans would not dare to attack them at the center of the Dutch colony. However, Kieft and the settlers realized that this was a unique opportunity to strike against the “wilden”. Both Kieft and the settlers believed that God had driven the Munsees into the hands of the Dutch so that they could rightfully punish them for the murders of the past few years. With God on their side, Kieft, the soldiers, and the settlers prepared for their nighttime attacks of February 25, 1643.

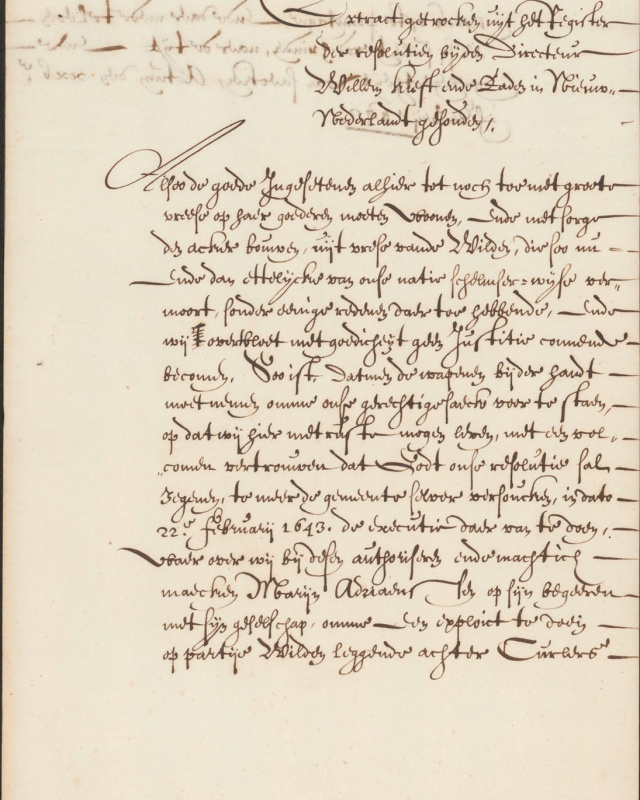

The instructions for the nighttime attacks are surprisingly well documented. In the archives of the States General are the “Extracts from the register of resolutions kept by Director Willem Kieft and Councilors in New Netherland.” Dated February 25, 1643, the resolution states how the settlers in the region of Manhattan have recently developed great fear for the “wilden” because they had recently killed several settlers. “In order that we may live here quietly,” Kieft and the council of New Netherland authorized Marijn Adriaensz and his companions to attack a group of Munsees who were residing at Corlaer’s Hook, “and to do with them as they consider advisable, according to the time and circumstances.”

In the detailed council minutes of New Netherland of the same date, currently housed in the New York State Archives in Albany, Kieft and the council also authorize a group of soldiers led by sergeant Rodolff to cross the river to Pavonia “to strike the wilden who are located behind Jan Eversen’s plantation, but to spare the women and children.” In the anonymous manuscript Journal of New Netherland, which contains a brief narrative account of the massacres most likely written by Kieft himself or someone close to him, for instance secretary Cornelis van Tienhoven, the soldiers returned to New Amsterdam with thirty Munsee prisoners. However, according to the anonymous authors of a pamphlet published by critics of Kieft in 1649, the soldiers did not spare anyone during their assault at Pavonia. Moreover, the council minutes, to which Kieft had direct access, also do not make any mention of Munsee captives being brought to New Amsterdam. It appears that the soldiers simply ignored the instructions. This would not have been the first time that company soldiers had disobeyed orders. During the punitive expedition against the Raritans in 1640, soldiers had killed several Raritans against the wishes of Van Tienhoven who was leading the attack. Clearly, the soldiers in New Netherland had no qualms about killing the Munsees.

Peer Pressure

A third and final factor that made the massacres possible was the group dynamic among the perpetrators. This is admittedly difficult to prove since we do not have detailed testimonies from the soldiers and settlers who participated in the events at Corlaer’s Hook and Pavonia. However, as Christopher Browning convincingly argued in his study of the ordinary Germans in occupied Poland during the Holocaust, peer pressure played a critical role in inducing soldiers to kill non-combatants. Reluctant soldiers felt compelled to participate in mass shootings because they did not want to be ostracized by their colleagues in a hostile environment. A similar dynamic was at work in New Netherland. In the early 1640s, New Netherland was a vulnerable colony surrounded by numerous Indigenous nations as well as by unpredictable English, Swedish, and French colonies. Once Kieft and the advisory board members resolved to launch the attacks, it was difficult for individual soldiers and settlers to shirk their responsibilities. Soldiers or settlers who refused to participate risked isolation in the colony. The only settlers who spoke out against the nighttime attacks were a handful of prominent individuals who did not actively participate in the massacres. Through the combination of strongly held negative views of Native Americans, the escalation of Dutch-Munsee hostilities, and peer pressure, the soldiers and settlers murdered a large number of Munsee men, women, and children in February 1643. . Interestingly, many settlers turned against Kieft after the slaughter of the Munsees. However, they did so after surviving Munsee groups launched devastating retaliatory attacks. In March 1643, Munsee warriors killed a number of settlers and torched many colonial farms across the wider Manhattan region. Even though most settlers had supported and participated in the massacres, they now blamed Kieft for having plunged the colony into chaos and devastation.

The massacres of February 1643 were no doubt a shameful episode in the history of New Netherland. How should people in the contemporary Netherlands place these events from almost four hundred years ago in the larger history of Dutch overseas expansion? One way to think about this question is to consider what the massacres mean for Munsee people today. Contemporary Munsees have not forgotten about the massacres at Pavonia and Corlaer’s Hook. In an editorial published in the Native American newspaper Indian Country Today in 2013, the Shawnee-Lenape legal scholar Steven Newcomb discussed the massacres of 1643 in the context of the “centuries-long perpetration of genocide against our nations and people by Christian European colonizing powers.” In less strong terms, the Munsee-Delaware chief Mark Peters from Ontario in a recent video-lecture on Munsee history describes the massacres as events that contributed to the violent removal of the Munsees from their Manhattan homelands by 1700.

It is perhaps easy to dismiss the claim by Steven Newcomb that the Dutch were guilty of having committed genocide in February 1643. The Dutch did not target all the Native Americans in New Netherland and Munsee survivors fiercely retaliated against the Dutch in the aftermath of the massacres. However, from the Munsee perspective, the Dutch repeatedly targeted Munsee communities in which every member was at risk of being killed by soldiers and armed settlers. After the massacres, the Munsees living in the vicinity of New Amsterdam had legitimate reason to fear that the Dutch were trying to physically eliminate them. The effective resistance of the Munsees should not distract from the repeated willingness of the Dutch to use mass-violence against their Indigenous neighbors. The asymmetry between Dutch and Munsee violence is also evident from the overall death-toll of Kieft’s War. Most historians conclude that approximately 1,600 Munsees lost their lives from 1643 to 1645. In contrast, only a few dozen settlers were killed by the Munsees.

I am completing this blog on 25 February 2022, in the wake of the public presentation in the Netherlands of several projects examining the Dutch use of violence during the Indonesian decolonization war from 1945 to 1949. One of the main conclusions of the reports is that the Dutch government and military authorized the widespread use of “extreme violence” against Indonesian independence fighters and their supporters. The parallels with the Dutch massacres of the Munsees are striking. In both situations, the Dutch used mass-violence in which non-combatants were often killed. In both events, the Dutch justified the use of excessive violence by claiming that their opponents were culturally and racially inferior. Although violence was not the sole characteristic of Dutch overseas expansion across three centuries, the massacres of the Munsees and the war against Indonesian independence show that mass-violence against Native peoples was a recurrent phenomenon in the Dutch colonial world.

About the author

Mark Meuwese (PhD Notre Dame, 2003) is Professor of History at the University of Winnipeg. He is the author of Brothers in Arms, Partners in Trade: Dutch-Indigenous Alliances in the Atlantic World, 1595-1674 (Leiden: Brill, 2012) and To the Shores of Chile: The Journal and History of the Brouwer Expedition to Valdivia in 1643 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019).

About the blog series

This is the fourth installment in a monthly series of blogs telling stories from the rich history shared by the American and the Dutch peoples. Authors from both countries will present various stories of their own choosing, from a wide variety of perspectives, in order to provide the full picture of the triumphs and heartbreaks, delights and disappointments that took place throughout hundreds of years of shared history. Not all stories will be ‘feel-good history’, however. While the relations between the Dutch and the Americans have for the most part been stable and peaceful, their shared history contains some darker moments as well. Acknowledging that errors have been made in the past does not take away from the friendship but, rather, deepens it.

Illustrations

-

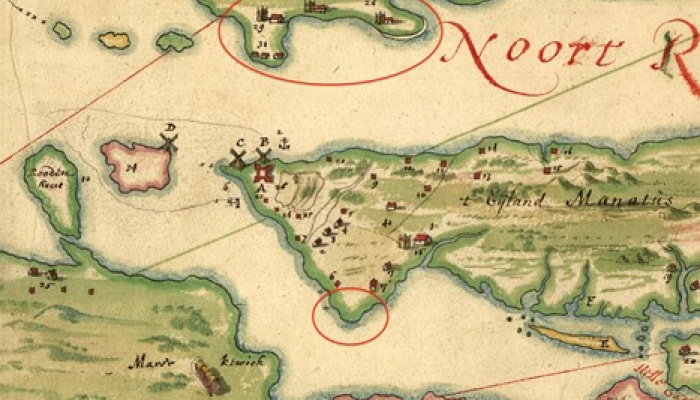

Detail of the Manatus Map, depicting Manhattan in about 1639, with north to the left. The locations of the two Dutch attacks of February 1643 are indicated by red circles. Library of Congress, G3291.S12 coll .H3. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3804n.ct000050?r=0.252,0.17,0.447,0.341,0

-

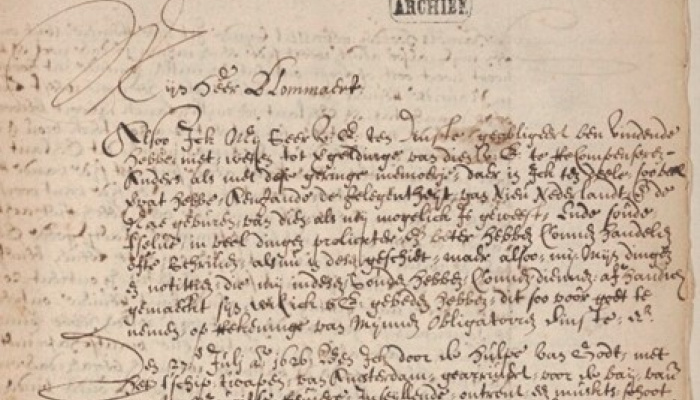

Description of New Netherland by Isaac de Rasière, addressed to Samuel Blommaert, ca. 1628, with an extensive section on the Native Americans on and around Manhattan. Nationaal Archief, collection 1.05.06, inv. nr. 2. https://www.nationaalarchief.nl/onderzoeken/archief/1.05.06/invnr/2/file/NL-HaNA_1.05.06_2_0009

-

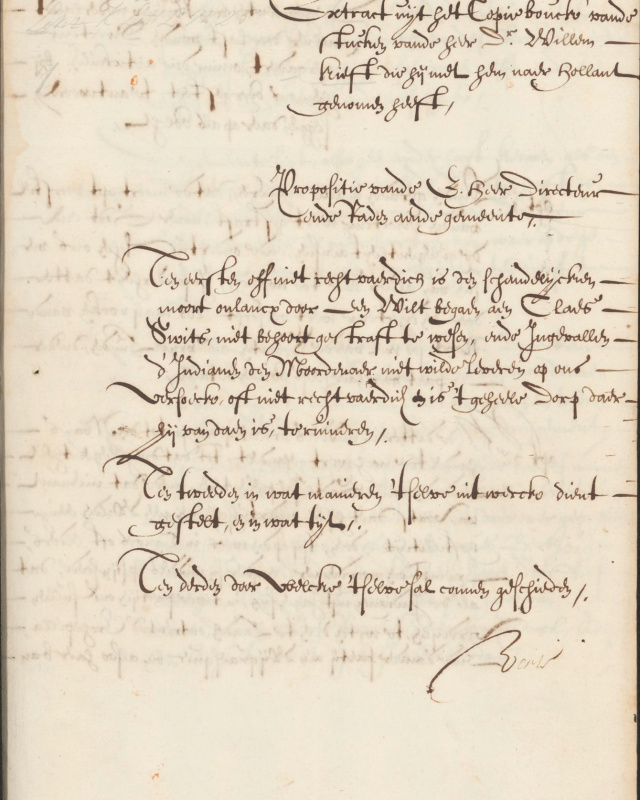

Proposition of Director Kieft to the commonalty, 29 August 1641. “First, whether it is not just that the scandalous murder recently committed by a wilt on Claes Swits ought to be punished, and, in case the Indians do not extradite the murderer at our request, whether it is not just that the entire village from which he originates be laid to waste?” Nationaal Archief, collection 1.01.02, inv. nr. 12564.25.

-

Resolution to grant Marijn Adriaensz permission to attack the Native Americans at Corlaers Hoeck, 25 February 1643. “Thus, at his request we hereby authorize and empower Marijn Adriaensen and his companions to make an attempt on a group of wilden located at Curlers hoeck or plantation, and to do with them as they consider advisable, according to the time and circumstances.”Nationaal Archief, collection 1.01.02, inv. nr. 12564.25.

-

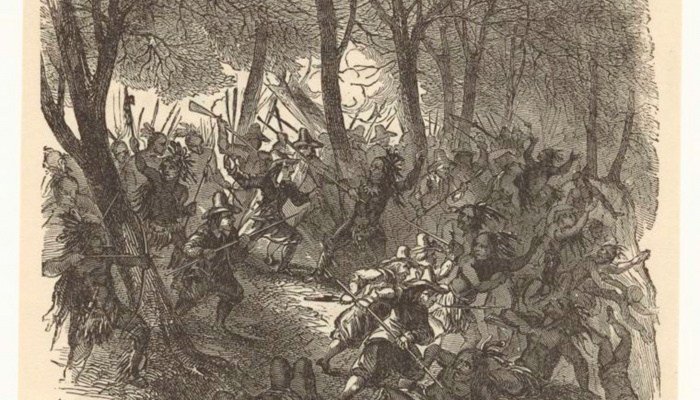

Illustration 5. A nineteenth-century depiction of the attack at Pavonia, included in Mary Louise Booth, History of the City of New York (New York: W.R.C. Clark, 1859), 113. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library.https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-0d38-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Further reading

- Browning, Christopher, Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland, revised edition (New York: Harper Perennial, 2017).

- Frijhoff, Willem, Wegen van Evert Willemsz. Een Hollands weeskind op zoek naar zichzelf, 1607-1647 (Nijmegen: SUN, 1995).

- Jacobs, Jaap, Een zegenrijk gewest. Nieuw-Nederland in de zeventiende eeuw (Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 1999).

- Lipman, Andrew, The Saltwater Frontier: Indians and the Contest for the American Coast (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015).

- Merwick, Donna, The Shame and the Sorrow: Dutch-Amerindian Encounters in New Netherland (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006).

- Otto, Paul, The Dutch-Munsee Encounter in America: The Struggle for Sovereignty in the Hudson Valley (New York: Berghahn, 2007).

- Schulte Nordholt, J.W., “Nederlanders in Nieuw-Nederland. De oorlog van Kieft met als bijlage het Journael van Nieu-Nederland,” Bijdragen en Mededelingen betreffende de Geschiedenis der Nederlanden 80 (1966), 38-94.

- Waterman, Kees-Jan, Jaap Jacobs, and Charles T. Gehring (eds.), Indianenverhalen. De vroegste beschrijvingen van Indianen langs de Hudsonrivier (1609-1680) (Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2009).

Sources

- Dutch National Archives, collection 1.01.02, archive of the States General, inv. nr. 12564.25.

- Dutch National Archives, collection 1.05.06, collection assorted West India documents, inv. nr. 2 (letter of Isaack de Rasière to Samuel Blommaert, director of the West India Company, comprising a description of New Netherland, undated. https://www.nationaalarchief.nl/onderzoeken/archief/1.05.06/invnr/2/file/NL-HaNA_1.05.06_2_0009

- Dutch National Archives, collection 1.11.06.14, inventory of digital duplicates of WIC archives, located at the New York State Archives, Albany, 1630-1682

- https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/Objects/11558

- History lectures by Chief Mark Peters, recorded in 2021, at: https://www.publichistoryproject.org/2021/09/02/munsee-history-from-14000-bp-to-1763/

- Steven Newcomb, “A Dutch Massacre of Our Lenape Ancestors on Manhattan,” Indian Country Today, August 24, 2013, updated September 12, 2018. https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/a-dutch-massacre-of-our-lenape-ancestors-on-manhattan